Here's How To Choreograph for Large Groups

Choreographer Matthew Neenan, who danced in Pennsylvania Ballet’s corps, was eager to include plenty of dancers in his first work for the company back in 1998. “As a corps member, I’d always been around large groups, and it excited me to get everyone in there!” says Neenan, who ended up using 20 dancers in his ballet. But with a large cast come a lot of complications—complications that can sometimes overshadow the fun of having all those dancers to play with. What are the keys to clutter-free, universally flattering large-group choreo? Here are a few creative and practical ways to devise choreography that will help you highlight your cast’s strengths.

Define Your Concept

Joanne Chapman, director of Joanne Chapman School of Dance in Brampton, ON, mounts production numbers every year for 55 to 115 dancers aged 5 to 18. Her cardinal rule is to find a clear theme—and stick with it. “From the beginning, you have to have a well-defined concept,” she says. “Make a decision about what you’re going to say, and stay true to that. If you’re trying to tell a story, you have to be very explicit—otherwise, it can end up looking like a highway at rush hour.” Her piece Drove All Night, for example, had a 35-

member cast, for which she constructed pure-jazz choreography, avoiding aerials and acrobatics because they would have confused the overall look. “With a large group, you can’t afford to get sidetracked,” she says.

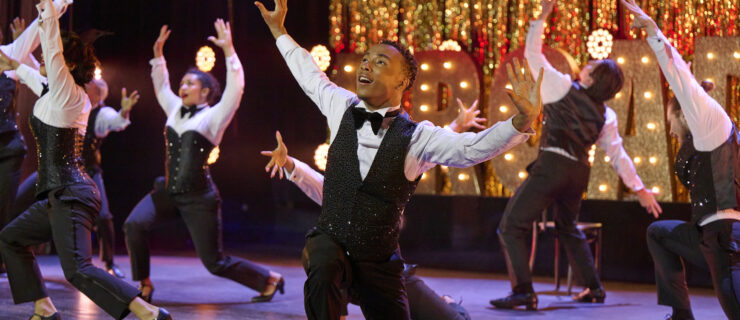

One of Suzi Taylor’s numbers for this year’s New York City Dance Alliance Nationals featured a cast of 145 (!) (Photo by Eduardo Patino, courtesy New York City Dance Alliance)

Emphasize Cleanliness

Even with a clearly defined concept, it’s easy for choreography to get muddy with a lot of dancers onstage. When teaching the steps, it’s important to be very specific about body alignment, arms, focus and direction changes. Chapman holds pre-planning sessions with her assistants to make sure everyone’s on the same page about the details. Then she rehearses her dancers in small groups, looking for inconsistencies and tightening up unison work.

Even if that kind of intense organization isn’t your style, it’s still smart to go into the studio with a battle plan. Though Neenan likes “to allow for some messes to happen, some bump-ins and such,” he still brainstorms big ideas and traffic patterns before beginning rehearsals. Mistakes, he says, are part of the journey. Just make sure that you take an active role in correcting and reshaping them.

Be Sensitive to Technical Levels

Inevitably, the range of abilities within a big cast will vary. Subdividing the piece into sections based on technical level can help you show each group’s strengths. But when the whole ensemble comes together, it can be helpful to keep the level of difficulty relatively low.

That doesn’t mean choreography for the whole group can’t be interesting. Chapman makes even simple phrases exciting by inserting featured moments for her strongest dancers. “One dancer doing turns or acrobatic tricks while everyone else is on the floor, for example, can really spice things up,” she says. “We also do a lot of canons, with each line starting the same phrase on a different count. That creates a very cool wave effect.”

Anticipate Logistical Hurdles

Getting groups of dancers on and off the stage is one of the toughest challenges of large pieces. Chapman makes transitions between sections seamless by using a consistent movement (like a jazz walk) for all entrances and exits, and slightly overlaps their timing to ensure a smooth flow. Neenan sometimes likes to have dancers in his larger pieces exit with structured improv, so they still hold visual interest even while others are entering—a pleasingly layered effect.

The most glaring logistical issue when working with a large cast is how to fit everyone onstage. Standard tricks like staggered lines are useful, but sometimes you’ll need to think more creatively. For this year’s New York City Dance Alliance Nationals Senior Outstanding Dancer number, Suzi Taylor literally couldn’t get all 145 of her dancers to move onstage at once without colliding—but she ended up turning that to her advantage. “I used the space on the floor in front of the stage, working level changes with unison and creating ripples of movement,” she says. “It turned out to be pretty stunning!”

Sometimes asymmetry can be the most arresting way to arrange a large group of dancers. Neenan encourages thinking about the possibilities beyond traditional lines. “I like to put dancers in ‘communities’, sharing the stage in more of a normal, ‘street’ fashion, rather than symmetrical patterns,” he says. Those kinds of groupings have the extra benefit of allowing more dancers to share a small space. “And using space creatively can be part of how you develop your original voice as a choreographer,” he says. “There’s only so much vocabulary—this is another way put your stamp on something.”