Up Close and Personal: Intimate Choreography

Picture this: Three couples—one heterosexual, one lesbian and one gay—perform a whirlwind of passionate movement, with the dancers embracing, lifting and rolling over each other. Choreographed by Jeff Amsden for Broadway Dance Center’s 25th Anniversary Gala last May, their dance portrays that nerve-racking, exciting moment in a relationship just before the first “I love you.”

You’d never know from watching her that 23-year-old Heather Romot, one-half of that female couple, is straight. “When Jeff asked me to do the piece, he said, ‘You’re going to be a lesbian—is that okay?’ I knew it would take some acting, but that’s my job as a dancer,” explains Romot, a BDC intern at the time.

Despite some initial awkwardness in the rehearsal studio, Romot and her partner were able to develop amazing chemistry. “I tried to think of myself as really in this relationship, completely in love and wanting nothing more than to express it—even though it was toward a girl,” Romot explains. “You can’t just do choreography. You have to live inside the story.”

Sounds easy enough, right? Not necessarily. What if you have yet to experience a serious romantic relationship? Not only might you have to portray emotions you’ve never actually felt, but you might also have to touch your partner as if you were in love. (In some cases, this could mean an onstage kiss!) Even in an abstract piece, you could be given close partnering work that involves your bodies touching in unfamiliar or uncomfortable ways.

It’s normal to feel overwhelmed by these new levels of closeness—but that doesn’t mean it’s not possible to pull off an intimate piece, as Romot did, with confidence and professionalism.

Why Get Intimate?

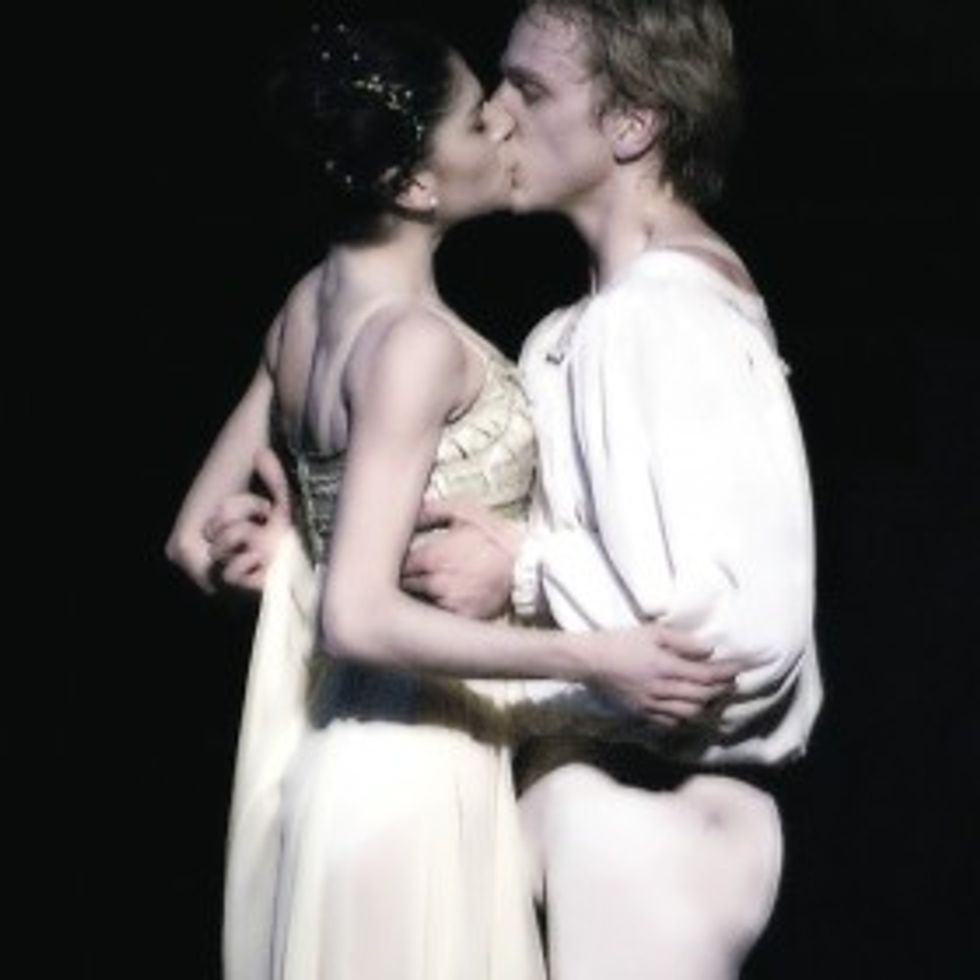

Showing affection onstage can take your performance to a new level. Done right—picture Jason Glover and Jeanine Mason’s kiss on “So You Think You Can Dance” Season 5—it will enhance the audience’s experience. “When you have chemistry with your partner, the storytelling is better,” explains musical theater choreographer Joshua Bergasse, who also teaches at BDC. “The audience will believe the relationship.”

You’ll also grow as an artist through the process of working closely with other dancers. You may become more comfortable in your own skin—which will in turn make you even more open with your partner. And you’ll become a better actor: “Jeff’s piece gave me a chance to play someone so different from myself,” Romot says. “Taking the chances I did in this piece helped me mature as a dancer and an actress.”

From Studio to Stage

Even the most beautifully intimate onstage moments may have had a rough start in the studio. Here DS helps you deal with four common intimacy hurdles.

1) Your partnership’s not the perfect match.

It’s fitting that 16-year-old Yvonne Lacombe’s first duet with her dance partner, Jonathan Doherty, was titled “At First Sight”—the two fell for each other shortly before the rehearsal process began! But after dating for two years, they broke up midway through rehearsals for a new love duet. How did the change affect their partnership? “It was awkward in the studio,” says Lacombe, who trains at Artistic Dance Conservatory in East Longmeadow, MA. “But we eventually let go and drew on the emotions we used to feel. After all, we still felt comfortable onstage together.”

Lacombe’s story shows that you don’t have to be in love with—or even attracted to—someone to have onstage chemistry. Finding common ground can help you come together. If you’re still not clicking with your partner after some time, try taking yourself out of the equation. “Think, ‘I’m not me—I’m this character who is close to this other character,’” advises Pilobolus Dance Theater member Christopher Whitney. “Then you can touch one another in whatever way is required. Even if you’re not friends, your bodies can be friends.”

2) You can’t relate to the emotions in the choreography.

Believe it or not, even if you’ve never actually gone through the specific experience you’re being asked to portray, you’ve probably have had relationships and life experiences that will help you understand how to show love and other intimate emotions onstage. “There are many different kinds of love and intimacy,” explains dance psychologist Harlene Goldschmidt, PhD. “You experience love, tenderness and closeness with siblings, friends, parents—even pets!” Envision someone you’re close to and put the feelings you have for that person into the choreography. Remember that the rehearsal process is a safe time to explore your emotional performance, because as with the actual steps, the more you practice portraying intimacy, the more comfortable you’ll be onstage.

3) Your partner’s body makes you uncomfortable.

What if your partner is really sweaty, or has body odor or bad breath? The best thing to do in this scenario is to speak up—gently. Consider how you would want to be told about a problem if the situation were reversed. Try to make light of the problem, and relate it to dancing so that it’s not perceived as a personal attack. For instance: “If your partner’s sweaty, say, ‘Hey, can I get you a long-sleeved shirt? I’m sliding off you!’” says Jen Abrams, a contemporary choreographer and contact improvisation teacher in NYC.

4) You’re being touched in all the wrong places.

If your partner’s hands are straying dangerously close to your private parts, assess his or her motives. “Is your partner’s intention to do anything other than execute the movement?” asks Abrams. “In that case, you might have cause to be uncomfortable. But it’s more likely that they don’t intend to touch you in that way. You’d be doing them a favor to let them know.” (If you do feel that your partner is touching you inappropriately on purpose, or if he or she doesn’t stop when you point it out, share your concerns with an adult. This type of touch is sexual harassment, and an adult can help you handle the situation.)

But what if the choreography requires you to touch in a way that you worry is “inappropriate”? Bergasse recommends approaching the movement from a choreographic—rather than emotional—perspective. “It’s like a math equation,” he says. “Break it down and analyze it: ‘My hand needs to go here, and your leg wraps around here. From there we do this.’ Once you know the movement, you can add emotion later.”

A major measure of success for any piece that portrays intense affection onstage is how immersed in it the dancers become. If you feel the emotions—live them—the audience will, too.

Just ask Romot, who won’t forget the experience of performing Amsden’s piece anytime soon. “When I think back to this dance, I can’t remember the exact choreography, but I remember the intense emotions I was feeling,” she says. “Onstage, I felt as though we were the only two people in the room.” Now that’s intimate.