Choreographing for Two

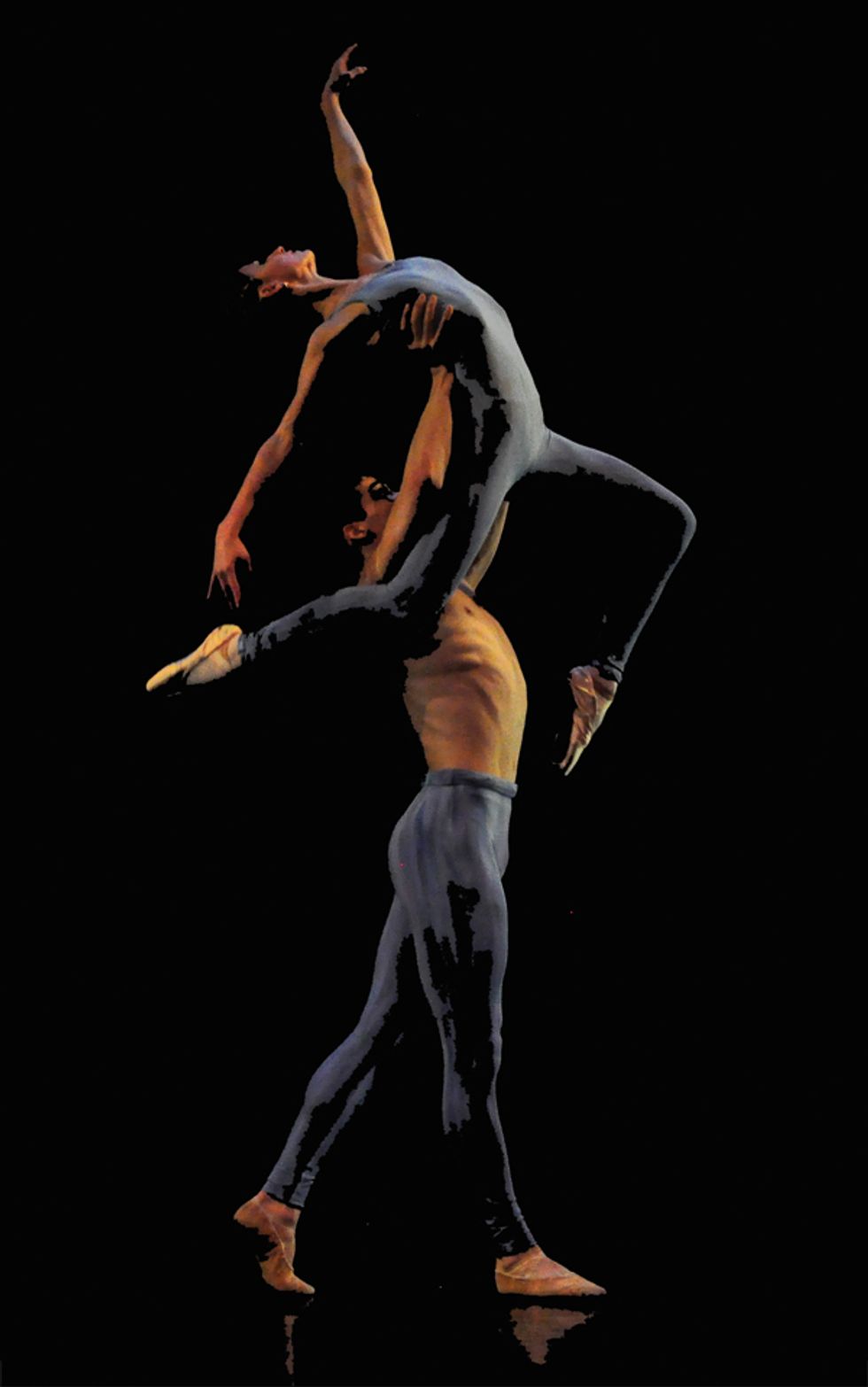

Andrea Bayne and Matthew Cluff in Bruce Monk’s Nocti Lux at Ballet Victoria (photo by Jean-François Mincet)

Sizzling tension, intoxicating romance, heart-wrenching drama: Whether we’re talking about a “So You Think You Can Dance” routine, the Black Swan pas de deux or a classic Fred and Ginger–style ballroom number, duets can pack a serious emotional punch. They can also wow us with their amazing lifts and other feats only possible through partnering. But creating a dance for two is uniquely difficult. How do you choreograph for two bodies in a way that’s flattering, balances tricks and artistry and leaves a lasting impression? DS talked to the pros to find out.

Before You Get to the Studio

Duets are, by their nature, relationship stories. So start by defining the tale your dancers will tell. “SYTYCD” and Broadway choreographer Joey Dowling likes to watch couples on the NYC subway—their body language and interactions often give her ideas.

And don’t be afraid to go beyond the typical love story. Shannon Mather, choreographer for “Dancing with the Stars” and director of Mather Dance Company, once made a duet for twins, with one as the “mind” and one as the “body.” Travis Wall is known for his powerful guy-guy duets for “SYTYCD,” like the Season 7 piece he made for Kent Boyd and All-Star Neil Haskell about two feuding friends.

Find a Balance

Good duets require a delicate balance of ingredients. Dowling calls it her “recipe”: “A good recipe has a dash of this and two cups of that,” she says. “In dance terms, you don’t want a work to be all partnering or two people doing side-by-side solos.”

It’s particularly important not to overstuff your piece with impressive lifts and forget about the quieter, simpler movements. “Remember to allow the duet to breathe—that’s when the chemistry between the dancers builds,” Mather says. “Sometimes it’s the moment when the two are just looking at each other, engaging with each other, that brings the audience in. Plan the big lifts, but the chemistry is what the audience will remember.”

Shannon Mather rehearsing Lonni Olson and Jace Zeimentz (photo by Tamerra Herres)

Play up the Dancers’ Strengths

Sometimes the biggest challenge when choreographing a duet is dealing with two dancers who aren’t exactly a match made in heaven. What if you’re working with a powerhouse technician and an emotional mover, or an experienced girl and a totally inexperienced guy—or two people who simply don’t get along?

If your dancers aren’t technical equals, don’t force it. “I’m never going to have two dancers pirouette at the same time if one’s a strong turner and the other’s not,” Dowling says. Pushing a dancer’s technical limitations is generally a good thing—but not when he or she is going to be closely compared to the only other person onstage. Instead, blend the dancers’ strengths by “restyling” or modifying their best tricks. “Don’t try to do an overhead lift with a guy who doesn’t have the technical experience needed,” Mather says. Instead, opt for a shoulder sit, a cradle or another simpler lift that still looks interesting. “You can find the ‘wow’ moment without breaking the girl’s neck,” Mather says.

Andrea Bayne and Matthew Cluff in Paul Destrooper’s Dances with Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (photo by Jean-François Mincet)

Dancers of different experience levels can actually be a blessing in disguise. Paul Destrooper, artistic director of Ballet Victoria in Victoria, British Columbia, loves the dynamic energy sparked by pairing a veteran with someone greener. “There’s a circle of learning and experience that’s unique in pas de deux work,” he says. “It can be tough and stressful, but it’s valuable for a mature dancer to mentor a newer one.”

Dealing with personality conflicts is stickier—but as the person at the head of the room, you’re the one who has to lay down the law. Dowling has “zero patience” for bickering. Make sure your dancers understand that personal differences must be put aside the moment they set foot in the studio. And there’s actually a certain heat between dancers who dislike each other. If you can, incorporate that into the choreography.