Japanese Classical Dance: The Inside Scoop on Nihon Buyo

A poised young woman stands completely motionless, balancing a branch of wisteria flowers over one shoulder. With the twang of a shamisen (a three-stringed instrument akin to a guitar), her head rolls in a languid figure-eight and her arms carve delicate shapes through the air. Within these first few captivating moments of Fujimusume (Wisteria Maiden), it’s clear why the 19th-century solo is arguably the most famous and popular work in nihon buyo—Japanese classical dance.

But beautifully stylized movement alone doesn’t tell the whole story of nihon buyo. From its origins in traditional forms of theater to modern-day performances, nihon buyo has always been about communicating a clear narrative through an intricate physical language.

Substance and Style

This refined form of visual storytelling emerged within Japanese kabuki theater in the early 17th century, thanks to the work of avant-garde female theatrical dancers. “The vast majority of dances that we know today were created to go with particular poems, legends, or stories set to music,” says Genkuro Hanayagi, a principal dancer in Geimaruza, Japan’s leading nihon buyo company. “So it makes sense that nihon buyo has very little abstract choreography, but a lot of concrete movement and pantomime.” In 1629, the Japanese government banned women from the kabuki stage, and nihon buyo evolved into an art form independent of the kabuki world.

No matter what story is being told, “we take a solid stance, lowering the center of gravity,” says Hanayagi. “We also frequently stamp our feet loudly on the stage, which comes from the folk dances that agricultural communities would perform as part of festivals and other religious occasions.” Even if you don’t know the backstories or understand the lyrics, “the choreography and production values of nihon buyo are spectacular,” says Kana Yamato, who’s based in Osaka and has toured to Paris and NYC with the all-female company Yamato Mai. “I never get tired of seeing all the rich and colorful costumes, choreography, and stage pictures.”

Training Grounds

Traditionally, professional nihon buyo performers have been born into the business. This was the case for Hanayagi: “Because my father was a master of nihon buyo, I was surrounded by that world from a young age,” he explains. “I then naturally began to walk the path of nihon buyo.”

But more and more dancers in Japan and beyond are starting nihon buyo without a family connection. “When I was in first grade, my parents put me in a children’s kabuki class to learn courtesy and etiquette,” says Yamato. Others discover nihon buyo as a way to forge a deeper connection with their heritage.

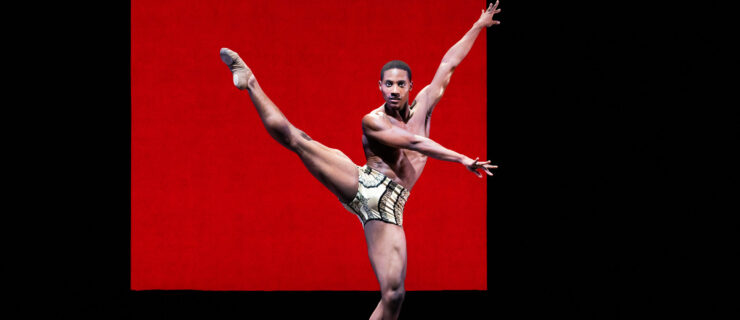

Genkuro Hanayagi dancing “Shirasagi-sho (Winter),” part of a longer work evoking the four seasons (courtesy Genkuro Hanayagi)

Genkuro Hanayagi dancing “Shirasagi-sho (Winter),” part of a longer work evoking the four seasons (courtesy Genkuro Hanayagi)

Tools of the Trade

Props and costuming are vital tools for nihon buyo performers. Experienced audiences can even identify the character a dancer is embodying by looking at the performer’s kimono and body language. “For example, the role of a young woman is called ‘musume,’ ” explains Hanayagi. “That dancer will always wear a kimono with long, dangling sleeves called ‘furisode.’ When the musume takes the furisode in both hands and drapes them across the front of her chest, that signals to the audience that she’s in love.”

Maybe the most versatile and expressive prop in nihon buyo is the folding fan. Hold it up in front of your chin and tilt your head back slightly, and it’s a cup from which to drink. Flip it upside down, gently fluttering the wrist (think jazz hands), and it becomes snow gently falling. This kind of specifically coded choreography has been passed down through generations of dancers.

Nihon Buyo in 2018

There are 5,000 professional nihon buyo dancers active in Japan today, and expat teachers offer lessons and perform in NYC, San Francisco, and other urban areas. Like many classical art forms, “nihon buyo has already responded to changing times,” says Hanayagi. “Dancers might wear Western clothing when dancing, perform to an orchestra or recorded Western music (instead of to traditional Japanese musical instruments), or collaborate with artists from other genres.”

Yamato hopes that nihon buyo will stay true to its core as dancers respond to globalization and other contemporary forces. “It’s not the technique but the spirit that’s important,” she says. “No matter how skilled you are, if that technique isn’t accompanied by meaning and emotion, you won’t be communicating anything to anyone.”

A version of this story appeared in the October 2018 issue of

Dance Spirit with the title “Japanese Classical Dance: Stories That Move.”