Just Beat It

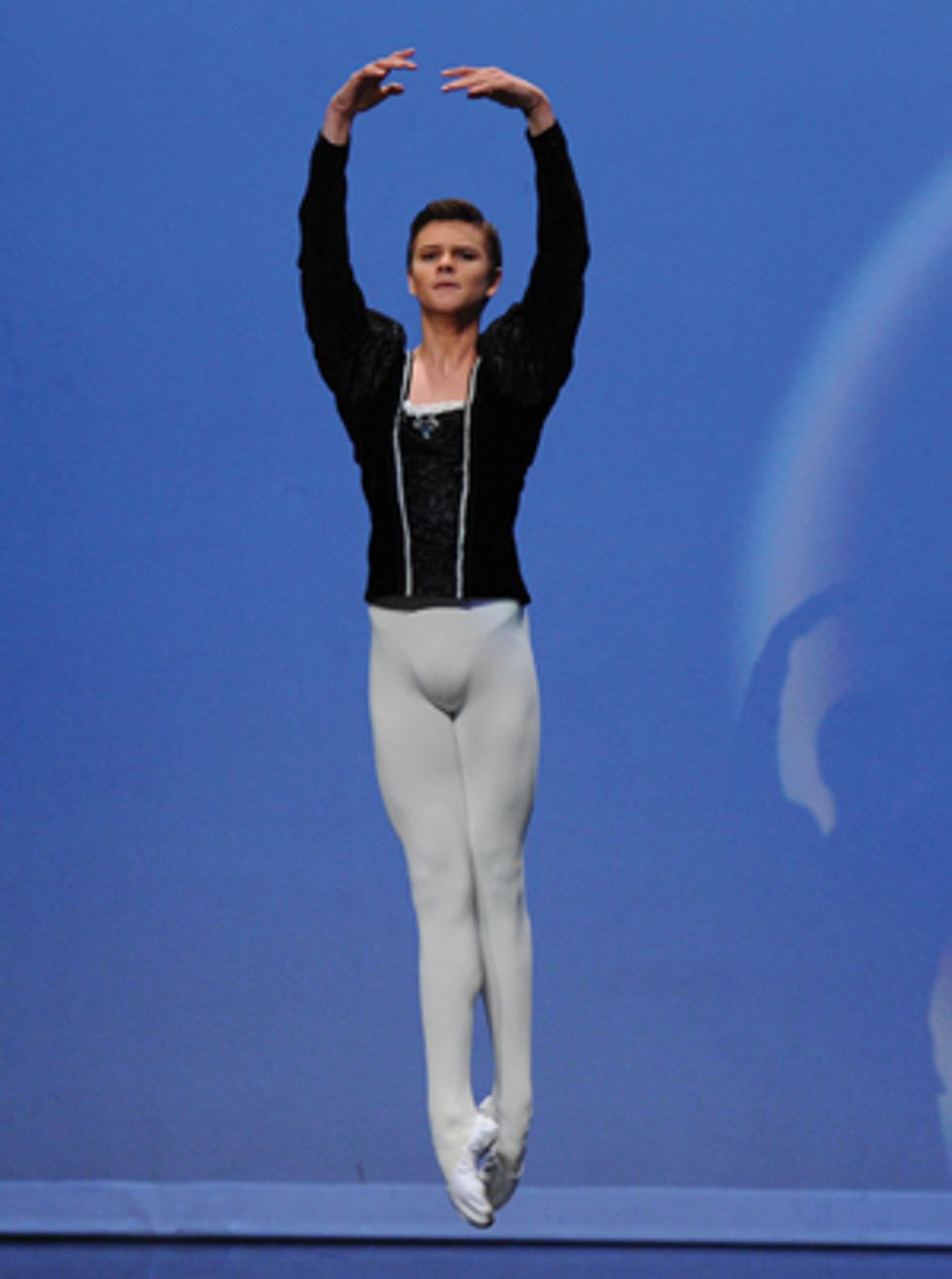

Former Patel Conservatory student Drew Nelson (Michelle Revels)

In Act II of Giselle, Albrecht does 32—32!—entrechats six in a row. His feet flutter like hummingbird wings as he hovers above the stage; you can almost hear them beating together. But how does he keep from getting tangled up? Surely the guy’s ankles are black and blue.

Not so, if he knows what he’s doing. Beaten jumps, called batterie, are a surefire way to impress a crowd—they give dancers that superhuman quality that makes audience members gasp. Like most jaw-dropping feats, batterie is difficult to master. But fear not: Once you have a good grip on the basics, the more complicated jumps will follow suit. DS asked three ballet experts to break down entrechats, the basic building blocks of batterie.

Entrechats by the Numbers

Entrechats are straight up-and-down jumps with varying numbers of beats. Their names indicate how many beats they include—but the way those beats are counted may seem tricky at first. Take an entrechat quatre (French for “four”), in which the front foot switches to the back in the air before closing in the front again. You may feel like that’s only two beats. But when you count the side-to-side movements—the front leg opens side (1), then closes back (2), opens side (3) and closes front (4)—the name makes more sense.

Creating the “Flutter Effect”

One common pitfall when attempting entrechats is to swing the feet back and forth, which eliminates that magical fluttery look. “Your legs should be moving sideways around each other,” says Peter Stark, artistic director of Next Generation Ballet and dance chair at the Straz Center for the Performing Arts’ Patel Conservatory in Tampa, FL. His students practice this exercise to identify the right muscles: Jump to second position, beat the legs in (right foot front) and land back in second. Repeat six more times, then beat front-back, landing in fifth, and start the exercise on the other side. “That helps you understand that your legs are coming in from the side,” Stark says.

PNB’s Lesley Rausch in Agon (Angela Sterling)

Alexander Peters, a Pennsylvania Ballet corps member, adds, “The beat shouldn’t initiate at your feet or ankles, but from the tops of your inner thighs.” That will create more space between your legs as they crisscross, resulting in a more impressive beat.

Entrechats Trois, Cinq and Six

Proper turnout is especially important when it comes to entrechats trois (which beat front before landing in sur le cou-de-pied back) and cinq (which beat back and front before landing in sur le cou-de-pied back). When dancers get caught up in completing the beats and forget to engage their turnout from the top of the leg, “the landing knee can end up in front of the landing toe,” Stark says—a mistake that can cause ankle and knee injuries. Hypermobile dancers are even more prone to strains and sprains after landing improperly. “I focus on using my lower abs, glutes and hamstrings when I land,” says Lesley Rausch, a (very bendy) principal dancer with Pacific Northwest Ballet. “Otherwise I’m just dumping all my weight into my ankle.”

Fast, articulate legs and feet are crucial to mastering the holy grail: entrechat six, which has six beats (back-front-back). All that beating can disintegrate into a wiggly mess. Stark uses a little trick to help his students with entrechat six: He tells them to think of it as a changement plus an entrechat quatre. “I say change, open-open, and then suddenly it becomes a beat.” Or, if it works better for you, think of it the other way around: a quatre plus a changement.

Peters offers a final word of entrechat advice, gleaned from teacher Andrei Kramarevsky at the School of American Ballet: Remember that you’ve been practicing the building blocks of batterie at the barre for years. “Think about the slicing movements of dégagés and tendus,” Peters says. “You’re just applying them en l’air.”