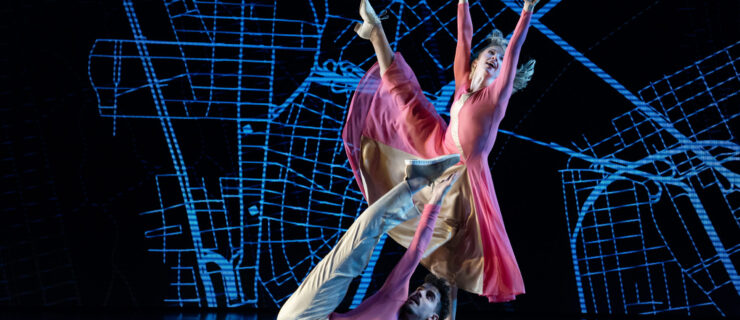

The Dance of Bulimia

In the spring of 2000, I felt like I had it all. I was 25, taking classes at Broadway Dance Center in NYC from amazing teachers like Michele Assaf and Mia Michaels, and had recently finished my second season as a Radio City Rockette in the Radio City Christmas Spectacular shows in Branson, MO. Moreover, I was about to become a New York Radio City Rockette—a dream I’d had since starting to dance at age 3.

But I was leading a dual life. Every day I performed in front of thousands of people, trying hard to maintain a façade of happiness. But in private, I was imprisoned by the shackles of bulimia.

Bulimia was nothing new to me. I had been in two hospital treatment programs prior to moving to New York—the second just three weeks before starting rehearsals for my first season of the Radio City Christmas Spectacular!

I started bingeing and purging at 15, after watching a movie on bulimia in health class. I had a muscular body, which I distortedly equated with being fat. During the prior year, I had become obsessed with dieting. I wanted to have a rail-thin body and was always trying to lose five or 10 pounds by restricting my food intake. I compulsively cut out pictures of models and ballet dancers from magazines as a motivation. But I loved to eat, so I’d break my starvation diet, which caused feelings of guilt and self-loathing—I thought I lacked self-discipline.

After seeing the movie on bulimia, I was awestruck and intrigued. I was sick of the shakiness, mood swings and hunger headaches that accompanied starving, so I tried purging. I quickly grew dependent on it. Within a year, I was out of control—bingeing and purging every day (even purging at the dance studio before class), and taking diet pills, diuretics and laxatives. What began as a game became my worst nightmare. I had no idea what I was up against, nor did I ever imagine that this addiction could rob me of my dance career, or, for that matter, my life.

During high school, I confided in my teachers periodically, and one was so concerned she called my mother. My mom was angry and demanded that I stop, which I agreed to do, but I couldn’t. By my senior year, I was purging several times a day and had to begin therapy. Although I loved talking to someone, my eating got worse.

Throughout the next 10 years, the disease escalated steadily and my life become increasingly unmanageable. When I was 19, I won a one-year scholarship to Tremaine Dance Center in L.A., and naively thought that a geographical change was the answer to my problems. But three days after arriving in L.A. I was bingeing and purging again. I began charging thousands of dollars for food on my parents’ credit card, stealing my roommate’s food and pawning anything I could to get money for more.

I didn’t understand why I couldn’t pull myself together. I was taking classes from people I idolized, dancing on cruise ships, appearing on “All My Children,” performing in Las Vegas, assisting Michele Assaf in Italy and dancing as a Radio City Rockette. But even my passion for dance couldn’t fill up the emptiness inside me. Finally the eating disorder started affecting my dancing. I missed auditions to stay home and binge and purge the day away. I hit bottom when I was performing at Radio City Music Hall in December 2000 and failed to show up for work. Until that day, I had never missed a dance job because of the eating disorder. I was in such a downward spiral that all I wanted to do was end my life.

I entered Sierra Tuscan, one of the best treatment programs in the country. During my 28-day stay at the resort-like psychiatric hospital, I went through intense group and individual therapy. The program focuses on learning healthy coping mechanisms and filling oneself up with spirituality instead of substances. It changed my life.

Almost six years later, I am 33 and living in Tampa, studying to become a social worker so that I can help people with eating disorders. While the obsession is no longer at the forefront of my mind trying to persuade me to self-destruct, its voice lingers. I wish I could say that I still dance. I tried to go back to the Rockettes, but on the first day of rehearsal, I landed in the hospital with meningitis and a kidney infection, and had to return to Tampa. I took that as a sign that it was time to hang up my dancing shoes.

Most people with eating disorders share certain characteristics and influences, and every therapist has said that I am a textbook case: extremely sensitive, a perfectionist and a people pleaser. My parents were extremely obsessed with food and dieting and believed that their weight was a measure of their success. We also didn’t talk about our feelings, my parents were constantly at war, and I felt like I had to provide happiness for our family. There is also a genetic component: Other people in my family have addictive behaviors. Lastly, being surrounded by mirrors every day in the dance studio didn’t help. I scrutinized every part of my body and compared myself to other dancers. Nonetheless, many dancers don’t have eating disorders, and someone else in my exact familial situation might not develop a problem.

Recovery is a mixed bag of tools. I go to 12-step meetings, work with a sponsor, journal, call people in recovery every day for support, do step-work, pray, read meditation books and follow a food plan. For the first three years after treatment, I used the tools daily. Now, my recovery is very laid-back. I almost feel like a “normal” person. I eat what I want and on most days that feels okay. My eating disorder stole my dance career from me, and while I do feel regret some days, I now turn my focus to helping others and keep the memories of dance alive in my heart.